Sailing Trip From Guatemala to Panama

October 26, 2011 to November 16, 2011

by Terry Welsh

Day 1

This has been your average travel day.

It began with Clara driving me to the airport in San Francisco. She was trying to have a conference call for work while I was complaining about her tailgating. She had her iPhone on speaker mode, but I could barely understand a word that her coworkers were saying. I held the phone near her ear, making me her hands-free device.

Clara is very jealous of my sailing trip adventure, and I will miss her. Hopefully she will become a proficient swimmer so that she can go on a trip like this in the future.

Adrian Agogino and I had the same flight from SFO, so we met by the boarding gate. It was an easy trip to Houston where we met up with Pierre Henry. Then we got our second flight to Guatemala City.

We had seats close to one another on the plane and conversed a lot with the other passengers. Everyone seemed excited to be going on vacation. I watched the in-flight movie Zookeeper, but it was too predictable and the sound was cutting out every few seconds.

After the flight I was talking to Crazy George. He is a member of the Magic Castle in Los Angeles and gave me a pass to get in. Maybe Clara and I can get a reservation and go next time we are in Claremont. George said he had worked as a baggage handler for United and now had some amazing amount of frequent flyer miles, so he travels the world giving magic shows at orphanages.

A fellow named Frankie picked us up at the airport in Guatemala City. It was a short drive to the Quetzalroo Hostel. They appear to run a good operation here. We got rooms and arranged a ride to the bus station tomorrow.

Pierre had a smoke on the roof and explained to me how to take a shower on a sailboat. You get a bucket of salt water, scrub yourself clean with it on the deck, and then rinse off with fresh water from the tank on board coming out a hose.

We tried to get a beer, but the refrigerator was locked up. Manuel, who runs the place, had already disappeared for the night. So I brushed my teeth and settled down on a couch in the hall to work on this journal.

My plan it to number each day as I write journal entries. Today is Wednesday, October 26, 2011, but I don't want to write down any more dates. I always feel more like I am on vacation if I can forget the date and day of the week.

Day 2

The bed in the Quetzalroo hostel was fairly comfortable and it was quiet, but I still only slept a tiny bit. Adrian, who I was sharing a room with, didn't even snore. He slept like the dead. Wonderful.

In the morning I got a quick cold shower. It appeared that there was an electric heater for the water, but I couldn't make it work.

Then I met Blanca in the dining area of the hostel. I believe she worked there, but I'm not certain. She was nice and made me some toast. Her English was about as good as my Spanish—quite poor. So we had fun communicating.

We got a few Quetzals from the ATM at the hospital across the street.

Marcos (I believe he is Manuel's brother) gave us a ride to the bus station. He told us a little about politics and corruption in Guatemala, but it was difficult to pick up details all the way in the back of the van.

The bus ride was a very uneventful seven hours, and we eventually arrived in Río Dulce. I believe Río Dulce is the name of the town, the region, and the river at this location.

Tom met us at the bus station and we headed off to buy provisions for the boat trip. I gather that "provisions" is the boating term for "groceries."

Tom Marlow is our captain, the owner of the boat, Ketch 22.

Tom and I rode Ketch 22 's dinghy back to Monkey Bay Marina. It's too small for four people, so Adrian and Pierre took a water taxi. Ketch 22 has been docked at Monkey Bay Marina for months or maybe a year.

Monkey Bay Marina is a pleasant place along the river, about a ten minute dinghy ride from Río Dulce. There have been problems with violent criminals in the past. In fact, a couple was murdered on their boat, which was anchored in Monkey Bay. Tom tells me that this was a crime perpetrated by the Queen of the River and her gang. Not to long after, the queen herself, her son, and two other gang members turned up dead.

Since Tom has been here (about the last four weeks), one dinghy has been stolen from Monkey Bay Marina and another from a nearby marina. This surprises me since Monkey Bay Marina is not accessible by land. You must arrive by boat.

Anyway, Tom's conclusion is that the locals will tolerate robbery, but not murder. It sounds like no tourists have been harmed since that last incident. At Monkey Bay Marina we wasted no time making margaritas for happy hour. I guess all the residents of the marina get together around sunset for a little social hour.

I was mostly speaking with the harbor master John. He has been at Monkey Bay Marina for eight years. He originally sailed from Florida and intended to settle in Aruba, but he found work here and remained.

John says this is the only place in the region that is sheltered from hurricanes. It has something to do with the way the wind flows out of the river valley into the Caribbean. He also says the best remedy for motion sickness is to sit down at the wheel of the boat and start steering. And never, ever go below deck—this will only make it worse.

When the mosquitoes became to annoying, we headed back to Ketch 22. We chatted about politics, the stock market, bad food in France, and all sorts of other nonsense.

Tom's wife Naty had told him that everyone was required to call home and tell their loved ones they had made it to the boat. Tom set me up with Skype on his computer and I called Clara. She has come down with a bad cold and didn't go to work today. Her interview for citizenship is tomorrow so I hope she feels better.

Tomorrow we set sail. Yeah!!

Monkey Bay Marina is a pleasant place along the river, about a ten minute dinghy ride from Río Dulce. There have been problems with violent criminals in the past. In fact, a couple was murdered on their boat, which was anchored in Monkey Bay. Tom tells me that this was a crime perpetrated by the Queen of the River and her gang. Not to long after, the queen herself, her son, and two other gang members turned up dead.

Since Tom has been here (about the last four weeks), one dinghy has been stolen from Monkey Bay Marina and another from a nearby marina. This surprises me since Monkey Bay Marina is not accessible by land. You must arrive by boat.

Anyway, Tom's conclusion is that the locals will tolerate robbery, but not murder. It sounds like no tourists have been harmed since that last incident. At Monkey Bay Marina we wasted no time making margaritas for happy hour. I guess all the residents of the marina get together around sunset for a little social hour.

I was mostly speaking with the harbor master John. He has been at Monkey Bay Marina for eight years. He originally sailed from Florida and intended to settle in Aruba, but he found work here and remained.

John says this is the only place in the region that is sheltered from hurricanes. It has something to do with the way the wind flows out of the river valley into the Caribbean. He also says the best remedy for motion sickness is to sit down at the wheel of the boat and start steering. And never, ever go below deck—this will only make it worse.

When the mosquitoes became to annoying, we headed back to Ketch 22. We chatted about politics, the stock market, bad food in France, and all sorts of other nonsense.

Tom's wife Naty had told him that everyone was required to call home and tell their loved ones they had made it to the boat. Tom set me up with Skype on his computer and I called Clara. She has come down with a bad cold and didn't go to work today. Her interview for citizenship is tomorrow so I hope she feels better.

Tomorrow we set sail. Yeah!!

Day 3

We didn't set sail. Darn! But we're working on it. Actually, I learned that the plan was not to set sail today. The plan was to motor most of the way to Livingston, the point at the end of the river where we check out of Guatemala. Actual sailing would happen on the following day after we were out in the ocean.

Anyway, none of that matters because it all went to hell anyway.

I went to bed with a budding headache and sore throat. It was probably a combination of dehydration and whatever Clara had when I left. There was a loud fan running below deck and it was far too hot with no air movement at all. I tried to sleep for hours, but to no avail. My assigned bunk was a small elevated slot with a cushion on the starboard side of the boat. It was tight and hard to climb into but would have been usable in the right conditions.

Eventually not sleeping and the head and my headache were too annoying. I sat on the dock and sipped water. At some point the local Monkey Bay Marina dog started barking. And then the neighbor dogs started up as well. I was being nearly silent, but dogs ears are awfully sensitive.

When my head felt a bit better I laid down on one of the benches by the steering wheel. It took a while but I got to sleep. Later I woke up because it was getting colder. Down below it was close to tolerable, so I got a little more sleep. But I was still up in plenty of time to see the sunrise.

When the day got rolling I took off the sail covers and did a few other small chores. The sail covers protect the sails when they are bundled up on the booms for long periods.

I learned that there are no ropes on sailboats, only "lines." Sailors have a lot of lingo that must be followed. In order to bundle up a line for storage, you arrange it as shown in Figure 1. First you coil up most of the rope into long, thin coils (about two feet long is normal), making sure to leave several feet to work with. With the remaining length, wrap the coils tightly four or five times. Poke a loop through the original long coils, and pass the end of the line through that loop. Pull the final loop and end tight. This will keep the line well organized and prevent it from becoming tangled with the other lines alongside which it is stored.

For bundling the sail covers for storage I used the knot shown in Figure 2. This allows you to make a loop that can be tightened but will not loosen as long as there is tension on the loop.

Actually, I did this with lanyards. Lanyards are like lines but much thinner. Tom has a collection of these on Ketch 22 just in case something random needs to be bound.

Tom and I took the dinghy to town to get some final provisions that we neglected to get the day before. We also picked up some fried chicken for lunch. There are a lot of fat people in Río Dulce. I wonder if it is partly due to the glut of fried chicken restaurants there.

Around noon we headed off on the boat. First we stopped for gas. We had set aside enough money to pay the customs fees when leaving Guatemala. With the remainder we bought some cold drinks because it was about 90°F and humid on the river. The store at the gas dock had everything we needed.

About an hour or two down the river, Tom announced that his voltage meter was not showing a high enough voltage and he was worried that the batteries weren't charging properly.

After a short time trying to diagnose the problem, Tom decided to turn the boat around. It was a bad idea to head out on the open ocean with a power problem.

We worked hard in the nasty heat of the engine compartment all the way back to Monkey Bay Marina. At some point we found that a part called a split charge diode had partly melted. It was used to protect the boat's two battery banks from one another in case one failed. We called it the red box because it was basically a big red metal heat sink with some electrical posts on it for connecting wires.

Tom took the busted red box to the local marine parts store, but they said it would take two or three weeks to get a new one. A local boat expert at Monkey Bay said we could bypass the box entirely. If we needed to use the backup battery, we would just have to switch to it manually by rewiring.

Tom and Adrian got to work on that, but it didn't fix the problem.

Pierre made Chicken Adobo for dinner, and Tom made margaritas. Mmmmm.

Things were looking dire. We had measured the voltage on everything in the electrical system and studied manuals for the different parts. Eventually, Tom replaced the alternator belt, which Adrian had noticed was showing its age. That fixed it.

Hurrah! We're back in business. It was well after dark by this point. Everyone was wiped out but elated about finding a solution. Up to that point it was really looking like the end of the sailing adventure.

We reformulated our plan and decided to leave early the next morning so that we could check out of Guatemala and catch up with our original schedule.

Boats are maintenance nightmares. Of course, Tom had thoroughly tested all the boat systems during the four weeks he had already spent on the boat. Problems like this tend to show up at the worst possible time.

Day 4

Tom and Pierre and I were up before sunrise. I enjoyed one last shower at Monkey Bay Marina. They had pretty nice showers and bathrooms for a random marina on the side of a river in Guatemala.

Adrian work up when we started the engine. It sure would be nice to sleep as easily as he. I probably slept for an hour above deck and an hour below deck.

All systems were nominal, so we motored all the way to Livingston. This took us all the was up the Río Dulce river valley. We saw cliffs, dense jungle, many types of birds, and hundreds of riverside dwellings. Most of these were small houses with rooftops made out of the reeds that grew all around the river. Many of them were accompanied by docks and boat houses. We saw plenty of fishermen paddling their kayaks and throwing nets. There were also tourists, commuters, and schoolchildren cruising around in motorboats. The children appeared to be riding the river version of school buses.

In Livingston I chauffeured Tom and Adrian to shore in the dinghy. They checked us out of Guatemala customs and got more fried chicken for lunch from Super Pollo Express.

Some of the people at Monkey Bay Marina had told me that a sailing trip is about 50% motoring. They were right. We motored all the way from Livingston and headed for Roatán. I took the first watch and took us into the Bay of Honduras, around Cabo Tres Puntas.

Pierre made an excellent salad for supper from fresh vegetables, hard boiled eggs, and some sort of balsamic-vinegar based dressing that he whipped up. I would like to try cooking on the boat, but I still have a cold and should stick to washing dishes for the time being.

Pierre grew up in Algeria and France. His family left Algeria when he was six, a few years before the revolution. His parents thought things were getting too violent. He was also lived in Fresno and Sacramento, so he has had a wide range of culinary influences. He clearly likes to cook, and I suspect that's one of the reasons Tom invited him along.

I tried to get a couple hours of sleep before my next watch, but it was pointless. I'm a light sleeper and the diesel engine on the boat growls much to loudly.

My watch was between 8 and 10 P.M., well after dark. With four of us on the boat, we would each have two hours on watch and six hours off.

It was both exciting and serene to cruise past the Mosquito Coast with nothing around but water. As the boat stirred up the water, bioluminescent creatures sparkled with a light green hue. I could see the glow of cities about twenty miles south on the coast of Honduras. It was too far away to make out individual city lights most of the time.

The purpose of the watch is to keep us on course and prevent us from colliding with other boats or anything else in the water. About a third of the way through the watch, a bright light appeared almost directly ahead on the horizon, al little to the left.

It took five or ten minutes for me to detect any change in brightness or position, suggesting that it was very large.

When traveling at a constant speed and heading, you can line up an object on the horizon with some part of your own boat. If you detect no parallax between these things, then the object is either headed directly away from you or, more likely, directly toward you.

Boats have nav lights. There is a red light on the port side (left), and a green one on the starboard side (right). Depending on which light or lights you can see and their orientation to one another, you can tell which way the boat is facing.

All of this is useful information for avoiding collisions. The object I was watching very slowly drifted to the right, but this can be difficult to detect on a small boat that sways much. It took about a half hour to actually pass it. The radar screen on Ketch 22 showed it as being a little over two miles away. It had the pattern of lights shown in Figure 3. Unfortunately it was too dark out to see any other features.

The two top lights were extremely bright, and this was an enormous vessel. I thought it was a cruise ship, but Pierre later told me that they light up like Christmas trees, even at night. This was probably a barge or tanker.

Only one other boat passed during my watch, but it was much smaller. It's neat to think they are watching you the same way you are watching them.

Tom came up out of the cabin for his watch, so I didn't need to wake him up. I showed him the one boat to the south that was already moving past us. I tried to go below and sleep, but it was pointless as usual. With the boat moving at a steady five or five and a half knots, there was a good breeze moving from the hatches to the back door. But, somehow, the air in the port and starboard sleeping bunks was still and hot.

All systems were nominal, so we motored all the way to Livingston. This took us all the was up the Río Dulce river valley. We saw cliffs, dense jungle, many types of birds, and hundreds of riverside dwellings. Most of these were small houses with rooftops made out of the reeds that grew all around the river. Many of them were accompanied by docks and boat houses. We saw plenty of fishermen paddling their kayaks and throwing nets. There were also tourists, commuters, and schoolchildren cruising around in motorboats. The children appeared to be riding the river version of school buses.

In Livingston I chauffeured Tom and Adrian to shore in the dinghy. They checked us out of Guatemala customs and got more fried chicken for lunch from Super Pollo Express.

Some of the people at Monkey Bay Marina had told me that a sailing trip is about 50% motoring. They were right. We motored all the way from Livingston and headed for Roatán. I took the first watch and took us into the Bay of Honduras, around Cabo Tres Puntas.

Pierre made an excellent salad for supper from fresh vegetables, hard boiled eggs, and some sort of balsamic-vinegar based dressing that he whipped up. I would like to try cooking on the boat, but I still have a cold and should stick to washing dishes for the time being.

Pierre grew up in Algeria and France. His family left Algeria when he was six, a few years before the revolution. His parents thought things were getting too violent. He was also lived in Fresno and Sacramento, so he has had a wide range of culinary influences. He clearly likes to cook, and I suspect that's one of the reasons Tom invited him along.

I tried to get a couple hours of sleep before my next watch, but it was pointless. I'm a light sleeper and the diesel engine on the boat growls much to loudly.

My watch was between 8 and 10 P.M., well after dark. With four of us on the boat, we would each have two hours on watch and six hours off.

It was both exciting and serene to cruise past the Mosquito Coast with nothing around but water. As the boat stirred up the water, bioluminescent creatures sparkled with a light green hue. I could see the glow of cities about twenty miles south on the coast of Honduras. It was too far away to make out individual city lights most of the time.

The purpose of the watch is to keep us on course and prevent us from colliding with other boats or anything else in the water. About a third of the way through the watch, a bright light appeared almost directly ahead on the horizon, al little to the left.

It took five or ten minutes for me to detect any change in brightness or position, suggesting that it was very large.

When traveling at a constant speed and heading, you can line up an object on the horizon with some part of your own boat. If you detect no parallax between these things, then the object is either headed directly away from you or, more likely, directly toward you.

Boats have nav lights. There is a red light on the port side (left), and a green one on the starboard side (right). Depending on which light or lights you can see and their orientation to one another, you can tell which way the boat is facing.

All of this is useful information for avoiding collisions. The object I was watching very slowly drifted to the right, but this can be difficult to detect on a small boat that sways much. It took about a half hour to actually pass it. The radar screen on Ketch 22 showed it as being a little over two miles away. It had the pattern of lights shown in Figure 3. Unfortunately it was too dark out to see any other features.

The two top lights were extremely bright, and this was an enormous vessel. I thought it was a cruise ship, but Pierre later told me that they light up like Christmas trees, even at night. This was probably a barge or tanker.

Only one other boat passed during my watch, but it was much smaller. It's neat to think they are watching you the same way you are watching them.

Tom came up out of the cabin for his watch, so I didn't need to wake him up. I showed him the one boat to the south that was already moving past us. I tried to go below and sleep, but it was pointless as usual. With the boat moving at a steady five or five and a half knots, there was a good breeze moving from the hatches to the back door. But, somehow, the air in the port and starboard sleeping bunks was still and hot.

Day 5

I came up on deck when Adrian was just starting his watch from midnight until 2 A.M. There were dark clouds dead ahead. After a few minutes it began to rain and the sea became quite choppy.

Down in the cabin, I battened down the hatches. While there, I spied one of the soft swivel chairs mounted to the floor. I sat in it for about ten minutes hoping that sleep would come. It didn't work, and the extra rocking motion made me feel like I might get sick.

I snarfed down a piece of candied ginger to try to prevent any impending motion sickness. Then I went and stood on the ladder leading up to the deck. It was the best place to have a view of the horizon and stay out of the rain.

After the first line of storms the sky got crowded with scattered rainstorms and we didn't see stars again for hours.

Pierre's watch started at 2 A.M. By that point the rain had stopped, but the sea was still choppy. The waves and wind were coming from the north, and we were traveling east, so there was a constant rolling motion back and forth between -15 and 15 degrees. Or even -30 and 30 degrees on some of the bigger swells.

Since the rain had stopped I was trying to doze off on one of the benches next to the steering wheel. The breezy night air got me a lot closer to sleeping that the warm air below.

Oh, I almost forgot, during Adrian's watch we saw birds or bats whizzing around the nav lights at the top of the mast. We couldn't figure out why they were out there miles and miles from shore. Maybe the storms blew them there from some nearby island.

Around 2:30 Tom came up on deck and was impressed by the amount of wind. He said we should put the sail up. It was rainy and miserable, and there were more ugly dark clouds up ahead, and we were all way too tired, but apparently the wind was too good to pass up.

Tom grabbed a flashlight, hooked himself to the safety line that ran the length of the deck and went to the bow to prepare the mainsail. The main mast on a cat-ketch is all the way forward at the bow.

When he signaled, Pierre turned the boat north into the wind under engine power. This lets the wind slip past the sail without filling it so there is no extra tension on the lines to deal with.

I pulled the halyard (the line that hoists the mainsail) as far as I could by hand and then wrapped it around the winch for extra leverage. On Tom's signals I also had to pull and release tension on the reef line, which prevents the sail from raising to its full hight. I guess Tom thought there was too much wind for that or the storm conditions were too unpredictable.

This was all a messy, iterative process involving Pierre correcting our heading frequently, Tom tweaking the sail and lines, and me taking commands about which lines to put on the winches. The headlamp that Clara game me one Christmas proved its worth since I was using one hand on the boat to keep myself from getting knocked over while cranking the winches with the other hand. Unfortunately the bright lamp was lighting the lines just fine but blinding me from the horizon. This was a persistent problem inching me ever closer to sea sickness. And every time I stuck my head out for a new command from Tom I could hear him cursing at some boat part or see him vanish behind the water that was exploding up around the bow.

Maybe things would have been better if I knew how to sail or knew the names of all the lines.

About a half hour after we started the sail was raised. Pierre turned the boat back on course and cut the engine. Now we were cruising at about seven knots instead of five.

Tom and I got to work coiling up the lines that we had used to keep them organized. We were both winded badly from physical exertion and sleep deprivation. Before I finished coiling the halyard, I handed it to Tom and lunged for the side of the boat.

Sadly, I was stilled hooked to the safety line on the port side and knew I didn't have enough slack to make it to the starboard side. So I puked into the wind, getting about half of dinner in the water and the other half on my arm, the deck, and a little on Pierre's legs.

Once I caught my breath I used a bucked on a rope to collect sea water and clean things up. Pierre joked that I was going to tell everyone it was because of his dinner. I was just relieved that it took a full-on high seas adventure to finally get me sick.

Raising the sail had a strong stabilizing effect on the boat. It still moved up and down with the swells, but the rocking motion was drastically reduced. By the way, this only works with a sufficient amount of wind. If there isn't enough, the sail loses tension and the rocking motion returns.

I was in bad shape when my shift started at 4 A.M. Pierre let me try to doze off a little longer and then tried to explain some new considerations for watch while under sail. You can't make turns as sharp as you can under engine power, so course corrections to avoid other boats might take more thought. Also, big gusts could sometimes shut off the autopilot which maintained your heading.

I had a banana before I got started. We watched a big barge move by. It looked a lot like the one in Figure 3 on Day 4. On the choppy sea it was much harder to judge which way other boats were moving. We got to see more detail in this barge because the sky was starting to light up.

Now at a depth of thousands of feet, the water looked like dark blue paint, nothing like the greens, browns, and aqua colors you see at the beach. It was stunning, and I could stare at it for a long time.

When Tom started his shift at 6 A.M. I headed below to try to sleep again. It was cooler now and quieter without the engine. But there was much more motion than before. The ocean swells were about four feet tall with some rising to about eight.

I laid there for three hours, totally conscious. Ug. Why can't I get some sleep? At first it was very restful to just lie there, but it eventually became too annoying because of the rough sea.

Up on deck I hung out with Pierre and Adrian. We had passed Isla Útila and could see Roatán up ahead. At about six knots, the boat was rocking more than the night before and we had hours to go.

Adrian gave me some turkey jerky. I took one bite and threw up, this time over the downwind side of the boat. After recovering, I finished it and had a bottle of Gatorade too. It felt great to get something into my empty stomach.

Hours later we made it to Roatán. Adrian and I pulled down the sail and we motored into one of the bays.

Pierre made some excellent spaghetti and meat sauce. I cleaned up what everyone else couldn't. The last real meal I had had was twenty-four hours earlier, but I had expelled that one. I was HUNGRY.

After dinner I took a swim beside the boat and rinsed off the sea water with water from the boat's tank.

Now I'm finishing up a day and a half of journal entries. We're anchored in the bay where it's very quiet. We have not checked into Honduras yet so we're not allowed to just leave the boat and wander around. I can see the lights from the island and hear distant music from clubs.

Day 6

We woke up still anchored in French Harbor, but the boat had dragged to a different location in the harbor. Sleep had been sporadic with all the wind and rain knocking on the boat all night.

Tom talked to Jimmy the harbor master on the radio. Jimmy said it would likely rain all day long, so we decided to dock the boat in the rain instead of waiting all day for the rain to let up. We got quite wet, but that doesn't seem like a big deal anymore We docked at Fantasy Island, a beach resort on its own little sub-island separated from Roatán proper by a short bridge.

Adrian and I had a beer and waited for the restaurant in the hotel to open for lunch. I also sent some emails on Pierre's computer.

In the lobby we met a guy named Kurt who had left the Unites States because he thought the government was decaying and wanted to sail around looking for a better place to live. He sounded very well read and was extremely talkative. Tom and Pierre got tired of talking with him first, but Adrian and I kept going. He even joined us for lunch. I think he was quite lonely.

Later on he told us about the time he was having doubts about his marriage while hiking a very treacherous trail called Na-Pali Coast on the island of Kauai in Hawaii. He said he prayed for a sign to help him figure out what to do. A little ways down the trail he and his wife saw a fellow in jeans and a bright white shirt sitting on a boulder looking out to sea, and glowing. He was communicating telepathically with some whales out in the ocean, trying to reassure them that humans would get their act together soon and stop polluting the oceans and mucking up the planet. Kurt knew all this because the guy in white let him into his mind so that he could listen in on the conversation. When Kurt realized that this was Jesus, he wanted to bow down, but Jesus said he didn't like all the bowing stuff and basically told Kurt that everything would be alright.

As they walked away, Kurt and his wife exchanged a few words and realized that they had both concluded that the glowing man was Jesus. When they turned around he was gone. They went back to the boulder, but Jesus was nowhere to be found, and there was no place he could have gone to hide in such a short time. He had simply vanished.

Some time later, Kurt and his wife divorced. You meet the most interesting people while traveling.

Kurt had plenty of other stuff to say too. He liked to talk politics, hoping that Ron Paul would win the 2012 presidential election. He said the Fantasy Island owner was a businessman from Spain with a really expensive sixty-foot yacht. He was doing a poor job of running the resort because he had just invested a lot of money beautifying the resort grounds instead of repairing the hotel rooms. This is why there were so few people at the resort. Truly, the resort feels like a ghost town. Kurt also talked about another Spaniard docked at the resort on a semi-permanent basis. He is a drug addict who has been banned from most parts of the resort but still manages to pay his dock rent. He likes to befriend resort guests with the intention of leeching free drinks and meals off of them. We're told to watch out for that guy.

In the lobby we met a guy named Kurt who had left the Unites States because he thought the government was decaying and wanted to sail around looking for a better place to live. He sounded very well read and was extremely talkative. Tom and Pierre got tired of talking with him first, but Adrian and I kept going. He even joined us for lunch. I think he was quite lonely.

Later on he told us about the time he was having doubts about his marriage while hiking a very treacherous trail called Na-Pali Coast on the island of Kauai in Hawaii. He said he prayed for a sign to help him figure out what to do. A little ways down the trail he and his wife saw a fellow in jeans and a bright white shirt sitting on a boulder looking out to sea, and glowing. He was communicating telepathically with some whales out in the ocean, trying to reassure them that humans would get their act together soon and stop polluting the oceans and mucking up the planet. Kurt knew all this because the guy in white let him into his mind so that he could listen in on the conversation. When Kurt realized that this was Jesus, he wanted to bow down, but Jesus said he didn't like all the bowing stuff and basically told Kurt that everything would be alright.

As they walked away, Kurt and his wife exchanged a few words and realized that they had both concluded that the glowing man was Jesus. When they turned around he was gone. They went back to the boulder, but Jesus was nowhere to be found, and there was no place he could have gone to hide in such a short time. He had simply vanished.

Some time later, Kurt and his wife divorced. You meet the most interesting people while traveling.

Kurt had plenty of other stuff to say too. He liked to talk politics, hoping that Ron Paul would win the 2012 presidential election. He said the Fantasy Island owner was a businessman from Spain with a really expensive sixty-foot yacht. He was doing a poor job of running the resort because he had just invested a lot of money beautifying the resort grounds instead of repairing the hotel rooms. This is why there were so few people at the resort. Truly, the resort feels like a ghost town. Kurt also talked about another Spaniard docked at the resort on a semi-permanent basis. He is a drug addict who has been banned from most parts of the resort but still manages to pay his dock rent. He likes to befriend resort guests with the intention of leeching free drinks and meals off of them. We're told to watch out for that guy.

Fantasy Island has lots of critters roaming around. There are turkeys, geese, chickens, peacocks, capuchin monkeys, and guatusas. Guatusas are also known as wild island rabbits. They are brown and have the size and movement of rabbits, but they are shaped more like guinea pigs or rats with no tails and bulbous hind sections.

Fantasy Island has lots of critters roaming around. There are turkeys, geese, chickens, peacocks, capuchin monkeys, and guatusas. Guatusas are also known as wild island rabbits. They are brown and have the size and movement of rabbits, but they are shaped more like guinea pigs or rats with no tails and bulbous hind sections.

Before dark I sat down in an open air section of the lobby that looked out over the beach. I started reading Strain by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan, which Lisa loaned me a long time ago. I lked the first sixty-five pages a lot.

It's still raining, and a bat just flew through the lobby.

Before dark I sat down in an open air section of the lobby that looked out over the beach. I started reading Strain by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan, which Lisa loaned me a long time ago. I lked the first sixty-five pages a lot.

It's still raining, and a bat just flew through the lobby.

Day 7

I actually got some decent sleep last night, if not continuous. The boat was steadier the night before because it was anchored. Being anchored means that it will drift to point directly into the wind, the same direction from which the waves are coming. Since the waves are moving down the long axis of the boat, the boat has more stability. Last night the boat was docked and the waves were coming from the starboard, so it rolled a lot more than it had pitched the night before. Despite this, the bunks were much cooler—perhaps because we had only run the engine briefly in the morning—and I was able to sleep better.

Tom checked the weather again and was still of the opinion that we should depart Roatán on Day 8. Due to the fuel shortage (which was most likely the misidentification of Fantasy Island's delinquent fuel payments) we planned to travel to Guanaja, the next island available, slightly out of the way, but only about eight hours from Roatán.

We went to town to get lunch and groceries. Er, provisions. (Everything has it's proper name on a boat.) The cab ride was far too expensive. They charge per person. And Adrian lost his cell phone in the cab.

Adrian headed back to Fantasy Island in another cab to try to call his phone and maybe retrieve it. Pierre, Tom, and I went looking for lunch. The area we were in had a Pizza Inn, and a Bojangles, which is another fried chicken place that I believe originated in the southeast United States. We picked Pizza Inn. I'm afraid that I was duped by their deceptive marketing and thought we were in a Pizza Hut for a long time until Tom told me otherwise. (Their signage was a blatant rip-off of Pizza Hut's.) That explained why the pizza wasn't so good. We should have gone to Bojangles.

There is some awesome joke to be made here about the Pizza of the Caribbean, but can't think of it.

We got groceries provisions for five or six days and headed back to Fantasy Island in another overpriced cab. Adrian was waiting in the cockpit of Ketch 22. He had forgotten to get the key to the cabin from Tom. Ug.

Adrian got someone at the hotel to help him call the cab driver. The driver agreed to bring the phone to the hotel for US$30, about triple the price he would charge for the round trip cab fair. Adrian eventually got the phone back and found that the cab driver had made an eighteen minute phone call to some other part of Honduras, accruing enormous roaming charges, probably to discuss with a friend how much money to extort from Adrian. Assholes. Anyway, Adrian had been taking all his pictures on that phones so it would have been very annoying to lose it permanently.

I read a bunch more of Strain. It's still a good book.

That evening I made chicken curry for dinner. My cold is about gone, so we figure it is safe enough for me to make meals. Pierre seemed happy to get a break from chef duty and we had margaritas, of course. We had replenished our collection of spirits during the shopping trip earlier in the day.

Day 8

The sandflies were biting like crazy in the morning. We lost the boat key for a while but discovered it later in Tom's jacket pocket. I took a shower in the room Jimmy had given us a key to. It turns out that Jimmy the harbor master's full name is Jimmy Hendrix. All in all, it was a pretty standard morning in the Caribbean.

Sandflies are more commonly known as no-see-ems. They have an annoying stinging bite that leaves a little red welt, and they are very persistent. They're called no-see-ems because they are so small that you usually don't see them.

I managed to forget the day of the week and day of the month for a while, so this can technically be counted as a real vacation. However, it's difficult to remain ignorant of such information for long. For example, this morning I had to take my pills to prevent malaria, and that requires that I know it is one week since we flew to Guatemala. Also, you must track the time to know when your watches start and end, and it's difficult to look at my watch without noticing the date.

By all signs, Fantasy Island appears to be winding down and will soon close. Or maybe someone will buy it and make improvements. It's a veritable ghost town with about a dozen boats docked here and a dozen guests staying in the rooms. And Jimmy Hendrix will be gone soon, trading his boat for an RV. Kurt will be leaving too, off to have new adventures in Singapore and Borneo.

We motored away at 8:30 A.M., leaving Roatán for Guanaja. The ride was uneventful. Tom has equipped Ketch 22 with black mesh screen material around the cockpit, and it keeps him from burning on sunny days. Unfortunately, it does not work for me and I got a decent sunburn on my back.

Oh, there was one event worth mentioning. We were visited by dolphins who swam with the boat, staying just ahead of the bow. I counted six at one point, but I believe there were more. The pod played in front of the boat for about fifteen minutes before departing for other waters. I could almost touch them from the bow, but not quite.

By all signs, Fantasy Island appears to be winding down and will soon close. Or maybe someone will buy it and make improvements. It's a veritable ghost town with about a dozen boats docked here and a dozen guests staying in the rooms. And Jimmy Hendrix will be gone soon, trading his boat for an RV. Kurt will be leaving too, off to have new adventures in Singapore and Borneo.

We motored away at 8:30 A.M., leaving Roatán for Guanaja. The ride was uneventful. Tom has equipped Ketch 22 with black mesh screen material around the cockpit, and it keeps him from burning on sunny days. Unfortunately, it does not work for me and I got a decent sunburn on my back.

Oh, there was one event worth mentioning. We were visited by dolphins who swam with the boat, staying just ahead of the bow. I counted six at one point, but I believe there were more. The pod played in front of the boat for about fifteen minutes before departing for other waters. I could almost touch them from the bow, but not quite.

We could see Guanaja in the distance for most of the trip and finally arrived around 3 P.M. Guanaja is an island with, as far as we can tell, no roads. Everybody has a boat instead of a car and motors from dock to dock. There are about 8,000 people here. The main settlement is on a tiny island that floats in front of the main island. All you can see of the settlement is a lot of houses on stilts rising out of the water. You cannot see any of the land or coral at the heart of this settlement from the outside. Guanaja was settled this way originally so the inhabitants could keep away from the sandflies.

There are also docks and buildings dotting the shore of the main island, many small islands with buildings on them in close proximity, and houses on stilts out in the water that are only accessible by boat. The whole place reminds Adrian of the movie Waterworld. Our first stop was a floating gas station where we found plenty of diesel to fill the tanks.

That morning I had lashed four five-gallon fuel jugs to the deck along the port toe rail. Now I really hope my inexperienced rope work holds up. To accomplish that task I had employed a bowline knot (Figure 4), probably the most common knot on any boat. Use it to make a loop at the end of a roat that can hold onto anything. The harder you pull on the rope, the tighter the knot gets.

We searched for a place to anchor, but the depths on our charts were way off. Eventually we found a place that was reasonably shallow and dropped anchor. Then a fellow pulled up in a motorboat to see if we were alright. His name is Meyers, and he was accompanied by his girlfriend.

We could see Guanaja in the distance for most of the trip and finally arrived around 3 P.M. Guanaja is an island with, as far as we can tell, no roads. Everybody has a boat instead of a car and motors from dock to dock. There are about 8,000 people here. The main settlement is on a tiny island that floats in front of the main island. All you can see of the settlement is a lot of houses on stilts rising out of the water. You cannot see any of the land or coral at the heart of this settlement from the outside. Guanaja was settled this way originally so the inhabitants could keep away from the sandflies.

There are also docks and buildings dotting the shore of the main island, many small islands with buildings on them in close proximity, and houses on stilts out in the water that are only accessible by boat. The whole place reminds Adrian of the movie Waterworld. Our first stop was a floating gas station where we found plenty of diesel to fill the tanks.

That morning I had lashed four five-gallon fuel jugs to the deck along the port toe rail. Now I really hope my inexperienced rope work holds up. To accomplish that task I had employed a bowline knot (Figure 4), probably the most common knot on any boat. Use it to make a loop at the end of a roat that can hold onto anything. The harder you pull on the rope, the tighter the knot gets.

We searched for a place to anchor, but the depths on our charts were way off. Eventually we found a place that was reasonably shallow and dropped anchor. Then a fellow pulled up in a motorboat to see if we were alright. His name is Meyers, and he was accompanied by his girlfriend.

Meyers suggested a better place to anchor so we motored a bit farther on his advice. We anchored again beside a hotel on a big rock that rose above the water. Like many other structures here, this hotel is totally isolated by water.

Meyers pulled up again in his boat the second time we were dropping anchor and said he had meant to lead us into a nearby cove. It was sheltered from waves, contained some other sailboats, and had a good German restaurant and bar on short. It appeared to us that the local welcoming committee received kickbacks from the German restaurant. We told him thanks but said we preferred to not move the anchor again.

A little later another guy pulled up in another boat. This time it was Linden, also there to advise us of the German restaurant. We said we didn't want to inflate our dinghy, so Linden offered to give us a ride. Tom and Pierre didn't feel like going anywhere (they appear to be totally immune to cabin fever), but Adrian and I couldn't wait to sample the local culture. We climbed into Linden's boat and headed for shore with no idea how we would get back to Ketch 22.

We arrived at a dock with five or six other dinghies. Beyond the dock was a small lawn, and beyond the lawn was an open-air restaurant with a welcoming staircase in front. There was a second story on the building, perhaps a home for the proprietors.

Meyers suggested a better place to anchor so we motored a bit farther on his advice. We anchored again beside a hotel on a big rock that rose above the water. Like many other structures here, this hotel is totally isolated by water.

Meyers pulled up again in his boat the second time we were dropping anchor and said he had meant to lead us into a nearby cove. It was sheltered from waves, contained some other sailboats, and had a good German restaurant and bar on short. It appeared to us that the local welcoming committee received kickbacks from the German restaurant. We told him thanks but said we preferred to not move the anchor again.

A little later another guy pulled up in another boat. This time it was Linden, also there to advise us of the German restaurant. We said we didn't want to inflate our dinghy, so Linden offered to give us a ride. Tom and Pierre didn't feel like going anywhere (they appear to be totally immune to cabin fever), but Adrian and I couldn't wait to sample the local culture. We climbed into Linden's boat and headed for shore with no idea how we would get back to Ketch 22.

We arrived at a dock with five or six other dinghies. Beyond the dock was a small lawn, and beyond the lawn was an open-air restaurant with a welcoming staircase in front. There was a second story on the building, perhaps a home for the proprietors.

Speaking of the proprietors, we met Klaus and Annette first. They're a friendly couple who speak English very well with German accents. They moved from Germany many years ago and started a motorcycle tours company in mainland Honduras. Klaus showed us pictures of the company in an old periodical. Hurricane Mitch wiped out the business, and they eventually made their way to Guanaja.

Adrian said it was a real "island fever" kind of bar. I should ask him what that means sometime. There were about a dozen people there, all local islanders. The big tourism season is November and December, but we were a little early for it. People there spoke Spanish, English, and Island English. Island English was extremely difficult for Adrian and me to understand, sounding to me like English so heavily accented as to be unrecognizable.

Meyers and his girlfriend were there . He said that when people spoke to him with Island English he had learned to tune most of it out. It was too difficult even after listening to it for years. I played a game of pool with Meyers. Pool is popular on Guanaja, but there are only four pool tables, and this was the best one. It was a close game but Meyers won.

Annette made us an excellent meal. I had a pair of sausages with sauerkraut and homemade noodles. She was very fast, serving up drinks right and left and generally doing a good job at pleasing all the customers.

We also met Gar from Pennsylvania, a regular at the bar. He wore a bandanna on his head, looked like a reformed bike game member who had seen too many hard days, and lived on a sailboat anchored nearby.

The shrimp mogul and Oscar showed up later with twenty pounds of shrimp for Annette and Klaus. We never got the shrimp mogul's name, but he was a local seafood distributor, specializing in shrimp, lobster, and conch. He told us a lot of other stuff, but I could not understand most of his Island English.

Oscar had more to say than anyone but was also very difficult to understand. He had no concept of personal space and would be nearly spitting in you ear when he spoke to you sometimes. I don't know whether that is an island characteristic or a drunk characteristic.

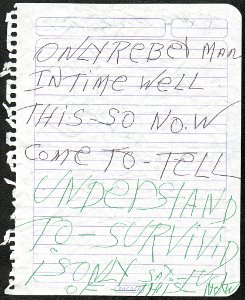

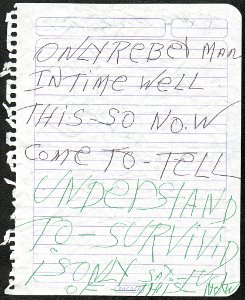

His full name is Oscar Albert, but he signs his name Oscar B. People in the bar call him Albert, Al, and Alby. He had a few important words to live by that he told me, such as "understand to survive," "keep up," and "time will tell." He has five daughters. There was a sixth, but she died in a storm or flood. He is forty-eight years old. It was very difficult to learn all of this since I had such a hard time with his Island English. "Understand to survive" sounds like "Ondastah to sahbeye."

Adriand was keen to find a ride back, remembering how early we had to renew our journey in the morning. Things on Ketch 22 get started at first light. Annette kept telling us we could get a ride whenever someone left, but Adrian was worried that nobody would leave for hours.

Eventually I asked around and heard that Marty, Meyers's brother, was leaving, so he gave us a ride back to Ketch 22 on his way. Meyers and Marty are a couple white guys (unusual for this island) who grew up partly in the Caribbean and partly in New Orleans. Their English had an unusual accent, but it was very easy to understand.

Speaking of the proprietors, we met Klaus and Annette first. They're a friendly couple who speak English very well with German accents. They moved from Germany many years ago and started a motorcycle tours company in mainland Honduras. Klaus showed us pictures of the company in an old periodical. Hurricane Mitch wiped out the business, and they eventually made their way to Guanaja.

Adrian said it was a real "island fever" kind of bar. I should ask him what that means sometime. There were about a dozen people there, all local islanders. The big tourism season is November and December, but we were a little early for it. People there spoke Spanish, English, and Island English. Island English was extremely difficult for Adrian and me to understand, sounding to me like English so heavily accented as to be unrecognizable.

Meyers and his girlfriend were there . He said that when people spoke to him with Island English he had learned to tune most of it out. It was too difficult even after listening to it for years. I played a game of pool with Meyers. Pool is popular on Guanaja, but there are only four pool tables, and this was the best one. It was a close game but Meyers won.

Annette made us an excellent meal. I had a pair of sausages with sauerkraut and homemade noodles. She was very fast, serving up drinks right and left and generally doing a good job at pleasing all the customers.

We also met Gar from Pennsylvania, a regular at the bar. He wore a bandanna on his head, looked like a reformed bike game member who had seen too many hard days, and lived on a sailboat anchored nearby.

The shrimp mogul and Oscar showed up later with twenty pounds of shrimp for Annette and Klaus. We never got the shrimp mogul's name, but he was a local seafood distributor, specializing in shrimp, lobster, and conch. He told us a lot of other stuff, but I could not understand most of his Island English.

Oscar had more to say than anyone but was also very difficult to understand. He had no concept of personal space and would be nearly spitting in you ear when he spoke to you sometimes. I don't know whether that is an island characteristic or a drunk characteristic.

His full name is Oscar Albert, but he signs his name Oscar B. People in the bar call him Albert, Al, and Alby. He had a few important words to live by that he told me, such as "understand to survive," "keep up," and "time will tell." He has five daughters. There was a sixth, but she died in a storm or flood. He is forty-eight years old. It was very difficult to learn all of this since I had such a hard time with his Island English. "Understand to survive" sounds like "Ondastah to sahbeye."

Adriand was keen to find a ride back, remembering how early we had to renew our journey in the morning. Things on Ketch 22 get started at first light. Annette kept telling us we could get a ride whenever someone left, but Adrian was worried that nobody would leave for hours.

Eventually I asked around and heard that Marty, Meyers's brother, was leaving, so he gave us a ride back to Ketch 22 on his way. Meyers and Marty are a couple white guys (unusual for this island) who grew up partly in the Caribbean and partly in New Orleans. Their English had an unusual accent, but it was very easy to understand.

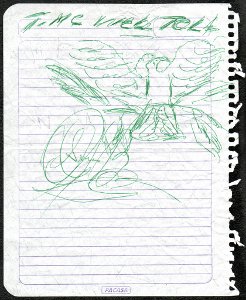

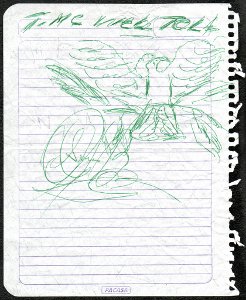

At some point in the evening, Oscar drew a pictures of an eagle on a napkin for me. Then he looked embarrassed and he tore it up. I was disappointed because I wanted to keep it for my journal. So a little later he borrowed another pen from Annette and created the masterpiece you see here. Below the eagle you may be able to make out his signature: Oscar B.

Of all the places I have seen, Guanaja feels the most like a completely different world. It is a floating island community that appears completely man-made from the outside surrounded by a largest island with jungle everywhere and too many sandflies, an island fueling station for travelers, a hodgepodge of islanders and expatriates, and probably one of the only places in the world where the only road is the water in the harbor.

At some point in the evening, Oscar drew a pictures of an eagle on a napkin for me. Then he looked embarrassed and he tore it up. I was disappointed because I wanted to keep it for my journal. So a little later he borrowed another pen from Annette and created the masterpiece you see here. Below the eagle you may be able to make out his signature: Oscar B.

Of all the places I have seen, Guanaja feels the most like a completely different world. It is a floating island community that appears completely man-made from the outside surrounded by a largest island with jungle everywhere and too many sandflies, an island fueling station for travelers, a hodgepodge of islanders and expatriates, and probably one of the only places in the world where the only road is the water in the harbor.

Day 9

I got a little sleep in the calm water at Guanaja. It would be the last for a while. Writing in this journal also had to take a break until the next harbor. It is too hard to write while underway. The motion on the open ocean prohibits it.

We motored out of the harbor at Guanaja around 6:30 A.M. Our destination was Vivorillos, a cluster of deserted islands near the corner of Honduras and Nicaragua, where we would turn and head south.

There was a small freighter on an intercept course with us at one point in the morning. Tom was a bit worried; I believe he is very wary of pirates. But this was an impractical ship to use for piracy, so I didn't think much of it. It was simply too slow to be a threat to anything but sailboats. Boats with valuables, such as yachts and sport fishing boats, could outrun it.

We were approaching a rain shaft, so we turned to port thirty degrees to try to pass behind the rain. Moments later, the freighter made a similar turn and was again on an intercept course with us.

This didn't bother me since it was a sensible move for the freighter to make to also avoid the storm. But the others on the boat were agitated.

Tom got on the radio and said something like, "Freighter on the horizon, this is sailboat Ketch 22. What is your intention?" By this point we could no longer see the freighter through the rain and clouds. We use a line-of-sight VHF radio on channel 16. Channel 16 is for general marine communications, but sometimes on it you will hear whistling, singing, people playing music, or long conversations. The only long conversation I have heard was in Spanish so I couldn't understand it.

The freighter finally responded and said it had changed course to avoid the rain. I was surprised anyone on board spoke English.

The next time we changed course to return to our original heading, the freighter did not follow us. It eventually drifted across our stern and over the horizon.

From Adrian and Pierre, I get the impression that Tom has a reputation among his peers as being extremely safe. He doesn't take unnecessary risks, and he has backups for almost every piece of equipment on the boat. He has more fuel filters than he can keep track of, and even a spare pump for the inflatable dinghy.

The wind picked up later in the day, so we hoisted the sails and shut off the engine. We were cruising at six or seven knots under sail, which is pretty good for a boat this size.

Pierre suddenly noticed that a steel ring connecting the end of the main boom to the deck had broken. When this rigging breaks, the boom can swing way too far and become a real problem. Lucky for us, the broken ring was still holding onto the rest of the rigging like a hook. It was a precarious situation, though. Tom grabbed a line out of his collection in one of the deck compartments and used it to lash the boom to the pulley at the end of the main sheet. (A sheet is a line that controls how much the boom is allowed to pivot.) This effectively replaced the broken piece of steel. It is not a permanent solution because there is too much chafing on a line used this way, but it should last until the end of the trip.

I tried cooking underway for the first time. The boat rolls a lot, so you have to constantly brace yourself with your feet and legs. It was very hot with the gas stove running so I was wearing only a swimsuit and sweating profusely. By the time I was finished preparing dinner I felt queasy, so I asked Tom to dish things up so I could go sit on deck for a while. Staring at the horizon helps me with motion sickness better than anything else. I recovered and had dinner.

While trying to sleep I noticed that from downstairs in my bunk the sea state feels much more rough than it actually is. For a while I thought it was getting stormy outside, but when I went up for a night watch it was smooth sailing.

Pierre suddenly noticed that a steel ring connecting the end of the main boom to the deck had broken. When this rigging breaks, the boom can swing way too far and become a real problem. Lucky for us, the broken ring was still holding onto the rest of the rigging like a hook. It was a precarious situation, though. Tom grabbed a line out of his collection in one of the deck compartments and used it to lash the boom to the pulley at the end of the main sheet. (A sheet is a line that controls how much the boom is allowed to pivot.) This effectively replaced the broken piece of steel. It is not a permanent solution because there is too much chafing on a line used this way, but it should last until the end of the trip.

I tried cooking underway for the first time. The boat rolls a lot, so you have to constantly brace yourself with your feet and legs. It was very hot with the gas stove running so I was wearing only a swimsuit and sweating profusely. By the time I was finished preparing dinner I felt queasy, so I asked Tom to dish things up so I could go sit on deck for a while. Staring at the horizon helps me with motion sickness better than anything else. I recovered and had dinner.

While trying to sleep I noticed that from downstairs in my bunk the sea state feels much more rough than it actually is. For a while I thought it was getting stormy outside, but when I went up for a night watch it was smooth sailing.

Day 10

Pierre has been dragging a fishing line behind the boat most of the time we have been underway. This morning we snagged a barracuda. It was about two feet long and had huge nasty sharp teeth. Tom said we can't eat barracuda because they can be poisonous.

We tried to coax it into shaking loose from the hook, but it didn't work. Finally Tom grabbed it with another general purpose hook on a pole and pulled it close enough that we were able to remove the fish hook with pliers. This took a few tries and was risky because the fish would thrash around a lot. I'm sure its teeth could have done a lot of damage to someone's hand.

Unfortunately, I don't think it survived the ordeal. It was very worn out and last time I saw it it was just floating away without moving.

The next fish we caught was about one foot long. We don't know what kind of fish it was, but it had red meat. Maybe it was some kind of tuna. Tom and Pierre cut it up on the deck, removing as much edible meat as they could. The rest of it went back into the water. Pierre washed off the deck with sea water.

We were near a shallow coral reef at this point, which is probably why we were finally able to catch something.

We arrived at Vivorillos around midday. This is a cluster of tiny islands that rise up out of a giant coral reef. The plan was to find sheltered waters in which to anchor and spend the night on a very calm boat. As we had been told at the German restaurant, there were many fishing boats working around the islands. I believe Vivorillos covers a large area and many of the islands are too far away to see.

We tried to coax it into shaking loose from the hook, but it didn't work. Finally Tom grabbed it with another general purpose hook on a pole and pulled it close enough that we were able to remove the fish hook with pliers. This took a few tries and was risky because the fish would thrash around a lot. I'm sure its teeth could have done a lot of damage to someone's hand.

Unfortunately, I don't think it survived the ordeal. It was very worn out and last time I saw it it was just floating away without moving.

The next fish we caught was about one foot long. We don't know what kind of fish it was, but it had red meat. Maybe it was some kind of tuna. Tom and Pierre cut it up on the deck, removing as much edible meat as they could. The rest of it went back into the water. Pierre washed off the deck with sea water.

We were near a shallow coral reef at this point, which is probably why we were finally able to catch something.

We arrived at Vivorillos around midday. This is a cluster of tiny islands that rise up out of a giant coral reef. The plan was to find sheltered waters in which to anchor and spend the night on a very calm boat. As we had been told at the German restaurant, there were many fishing boats working around the islands. I believe Vivorillos covers a large area and many of the islands are too far away to see.

We were close to two islands. One looked like your stereotypical tropical paradise island with white sand, palm trees, and glowing turquoise water around it. The other was covered in dark jungle vegetation and had fifty or a hundred frigate birds circling slowly above. There was a structure on the island that we think was an old military outpost. There was another more distant island to the north with very little vegetation and what appeared to be somebody's house. Maybe it was an old fishing shack that somebody stayed at on fishing trips.

We dropped anchor, but the location was not good. Too much wave action, and some of the rock formations in the water appeared too shallow.

We decided to try the east side of the islands instead and hope for better shelter from the ocean swells there. We would round the south side of the frigate bird island to get there.

On our way we passed a boat called the Yokey from Roatán. Its passengers wanted to talk to us and motioned us closer. Tom motored closer. The Yokey was some sort of small displacement hull river runner that appeared to be in use as a fishing boat. It did not look practical for the open ocean and would probably be better used as a water taxi. Its inhabitants were a scruffy bunch of shirtless fellows. I think I counted five, but Tom said there were more below. When we got closer they said they had a dead battery and needed a charge. Tom yelled that we didn't have the equipment to help them. When he saw that one of them had a line ready to tie our boats together he revved the motor and moved us away from them.

We were close to two islands. One looked like your stereotypical tropical paradise island with white sand, palm trees, and glowing turquoise water around it. The other was covered in dark jungle vegetation and had fifty or a hundred frigate birds circling slowly above. There was a structure on the island that we think was an old military outpost. There was another more distant island to the north with very little vegetation and what appeared to be somebody's house. Maybe it was an old fishing shack that somebody stayed at on fishing trips.

We dropped anchor, but the location was not good. Too much wave action, and some of the rock formations in the water appeared too shallow.

We decided to try the east side of the islands instead and hope for better shelter from the ocean swells there. We would round the south side of the frigate bird island to get there.

On our way we passed a boat called the Yokey from Roatán. Its passengers wanted to talk to us and motioned us closer. Tom motored closer. The Yokey was some sort of small displacement hull river runner that appeared to be in use as a fishing boat. It did not look practical for the open ocean and would probably be better used as a water taxi. Its inhabitants were a scruffy bunch of shirtless fellows. I think I counted five, but Tom said there were more below. When we got closer they said they had a dead battery and needed a charge. Tom yelled that we didn't have the equipment to help them. When he saw that one of them had a line ready to tie our boats together he revved the motor and moved us away from them.

I guess we will never know if they were a bunch of helpless fishermen or a group of casual pirates. All the fishing boats in the area were much better equipped to help them. On the east side of frigate bird island we even found a couple motorboats from the Honduran navy. They were anchored near the island and the crews were fishing. Maybe they should have been helping the Yokey.

We anchored again and the sea was still rough. Tom had expected more shelter from the Vivorillos islands.

With no way to get to land, potential pirates nearby, and on a boat that is steadier under sail, we decided to pull anchor and keep going.

For our next stop we had a choice of Providencia or San Andrés, both islands that belonged to Colombia, though they were much closer to Nicaragua. The timing suggested we would reach Providencia at night or San Andrés the following morning, so we set course for Andrés.

Later that day Tom pointed out that we had enjoyed a one hundred mile beam reach, something sailors love. A beam reach means the wind is hitting the boat almost directly from the side, which is optimal for the way sailboats work. Figure 5 shows a variety of other wind directions. It is impossible to sail in such a direction that the wind is between port close hauled and starboard close hauled. In this situation, you must tack, which is to sail in a zigzag pattern toward your destination, all the time keeping the wind at some usable angle behind close hauled.

We had sailed illegally through Honduras. The customs agent was unavailable the day we were in Roatán and we hadn't heard about an agent in Guanaja. Now we were out of Honduran waters and in Nicaraguan waters. Oh well. I suspect nobody will ever care.

We had our fresh fish for dinner.

I guess we will never know if they were a bunch of helpless fishermen or a group of casual pirates. All the fishing boats in the area were much better equipped to help them. On the east side of frigate bird island we even found a couple motorboats from the Honduran navy. They were anchored near the island and the crews were fishing. Maybe they should have been helping the Yokey.

We anchored again and the sea was still rough. Tom had expected more shelter from the Vivorillos islands.

With no way to get to land, potential pirates nearby, and on a boat that is steadier under sail, we decided to pull anchor and keep going.

For our next stop we had a choice of Providencia or San Andrés, both islands that belonged to Colombia, though they were much closer to Nicaragua. The timing suggested we would reach Providencia at night or San Andrés the following morning, so we set course for Andrés.

Later that day Tom pointed out that we had enjoyed a one hundred mile beam reach, something sailors love. A beam reach means the wind is hitting the boat almost directly from the side, which is optimal for the way sailboats work. Figure 5 shows a variety of other wind directions. It is impossible to sail in such a direction that the wind is between port close hauled and starboard close hauled. In this situation, you must tack, which is to sail in a zigzag pattern toward your destination, all the time keeping the wind at some usable angle behind close hauled.

We had sailed illegally through Honduras. The customs agent was unavailable the day we were in Roatán and we hadn't heard about an agent in Guanaja. Now we were out of Honduran waters and in Nicaraguan waters. Oh well. I suspect nobody will ever care.

We had our fresh fish for dinner.

Day 11

Trying to sleep is nearly pointless for me. Sometimes I can doze for a few minutes at a time, but there is no deep sleep. At night I lay down and do my best to rest, but I remain conscious. When we're in the calm water of a harbor I can sleep, but not while underway. It's either too hot and sticky in the bunk or, in this climate, too wet on the cockpit benches upstairs. I need to learn to be less of a light sleeper.

I'm still undecided on how I feel about cruising. The exhaustion is annoying. But the motion is very pleasant at times. The seemingly infinite ocean, colors of the water, storms, sunrises, and sunsets are very beautiful. The feeling of freedom is good, but it is squashed by needing to deal with customs agents and checking in and out of different countries. I'm told that customs agents can be very corrupt and try to get money from you to line their own pockets in a variety of different ways. Tom won't ever sail to Belize again after his experience there.

I asked Tom why he likes sailing. He most enjoys the life and death aspects of it. The big fish eats the little fish. And sailors sometimes eat fish if they can find them. And the whole time the sailor is at the mercy of the elements and trying to plan a journey that is survivable. He is in touch with his primal side out here in the ocean and he likes it.

I'm still undecided on how I feel about cruising. The exhaustion is annoying. But the motion is very pleasant at times. The seemingly infinite ocean, colors of the water, storms, sunrises, and sunsets are very beautiful. The feeling of freedom is good, but it is squashed by needing to deal with customs agents and checking in and out of different countries. I'm told that customs agents can be very corrupt and try to get money from you to line their own pockets in a variety of different ways. Tom won't ever sail to Belize again after his experience there.

I asked Tom why he likes sailing. He most enjoys the life and death aspects of it. The big fish eats the little fish. And sailors sometimes eat fish if they can find them. And the whole time the sailor is at the mercy of the elements and trying to plan a journey that is survivable. He is in touch with his primal side out here in the ocean and he likes it.

In the morning we floated through fields of garbage as far as the eye can see. By some phenomenon the garbage forms into long parallel lines across the surface of the water. I'll have to research how that happens after the trip. We couldn't think of a plausible source for that much garbage on the water. Can a storm blow that much out to sea? Did a cruise ship dump it? Who knows.

The wind grew too weak and Tom started the engine. This trip has been about half sailing, a quarter motoring, and a quarter motor-sailing. When the wind is too weak for good sailing you not only move slowly (for Ketch 22 that means down around four knots) but the boat also becomes unstable and rocks too much.

In the morning we floated through fields of garbage as far as the eye can see. By some phenomenon the garbage forms into long parallel lines across the surface of the water. I'll have to research how that happens after the trip. We couldn't think of a plausible source for that much garbage on the water. Can a storm blow that much out to sea? Did a cruise ship dump it? Who knows.

The wind grew too weak and Tom started the engine. This trip has been about half sailing, a quarter motoring, and a quarter motor-sailing. When the wind is too weak for good sailing you not only move slowly (for Ketch 22 that means down around four knots) but the boat also becomes unstable and rocks too much.

We moved into an area of heavy fishing activity. We would occasionally spot triplets of white floats that were marking nets or traps below. This area was relatively shallow, so we figured the fishing would stop when we reached the deep ocean again.

Around 10 A.M. we heard an ominous crunching sound. Tom immediately threw the motor into neutral and shut it off. Behind the boat we saw fragments of one of the fisherman's floats. Looking closer, we saw an intact float hanging out the back of the boat, and a line extending from under the boat down into the depths. We had snagged a fishing line on the prop.

Tom said this had happened to him once before in the Pacific and the only solution was to cut the line from the prop. I said I would go do it. Tom seemed concerned, asking if I was a strong swimmer. My swimming skill is fine, but I was certainly tired from lack of sleep. However, everyone on board was at least somewhat sleep deprived.

I put on the mask and snorkel (Tom had these on the boat because he is prepared for pretty much anything) and jumped into the Caribbean. This was a real zen moment. It was only about a hundred feet deep there, but that is far too deep to see the bottom. And we were miles and miles out of sight of land. Under the water I could see the bottom of Ketch 22, the weathered fishing line extending into the depths at a forty-five degree angle, and turquoise. Just pure, bright turquoise absolutely everywhere.

This would have been a great time to see some more dolphins, but there were none. Only turquoise.

There was a third float jammed up next to the prop, and it was connected to the one floating behind the boat. The line extending down to the depths was incredibly taught. We had been dragging it, and it probably carried a very heavy load underneath. I surfaced and said that we would need to cut the line. There was no hope of unwrapping it with that kind of tension. Tom handed me the knife, the same one that was used to prepare the fish we caught.

Back down in the turquoise I first made sure my limbs were clear of the downhill parts of the line. With that kind of tension I did not want to be tangled up in the line when it broke. I had my doubts about this knife. If the line could support this kind of weight, it should be exceptionally strong. But all I had to do was push the knife into the line. There was a muffled snap and the lower part of the line sped away into the deep. It was out of sight in a fraction of a second.

After another breath I got to work on the floats and the remaining piece of line tangled on the prop. I was able to unwrap the float and get it away from the prop. I worked the line back and forth like dental floss, but it was knotted up with seaweed in a confusing mass around the prop.

I grabbed onto the ladder at the back of the boat to take a break. The boat was moving up and down with the swells, and sometimes slapping down onto the water. So there was a lot of water moving around underneath and I was winded. The total lack of sleep for two nights probably didn't help either.

Tom decided to take a turn. Better to have a fresh person in the water instead of one who is worn out. I gave him the mask and knife and he jumped in. He swam under until we could just see his feet sticking out the back of the boat. After a bit of wriggling around he came back up. He had successfully cut the line off the prop.